Learning Can Be Fun...

But fun shouldn't be the goal of schools

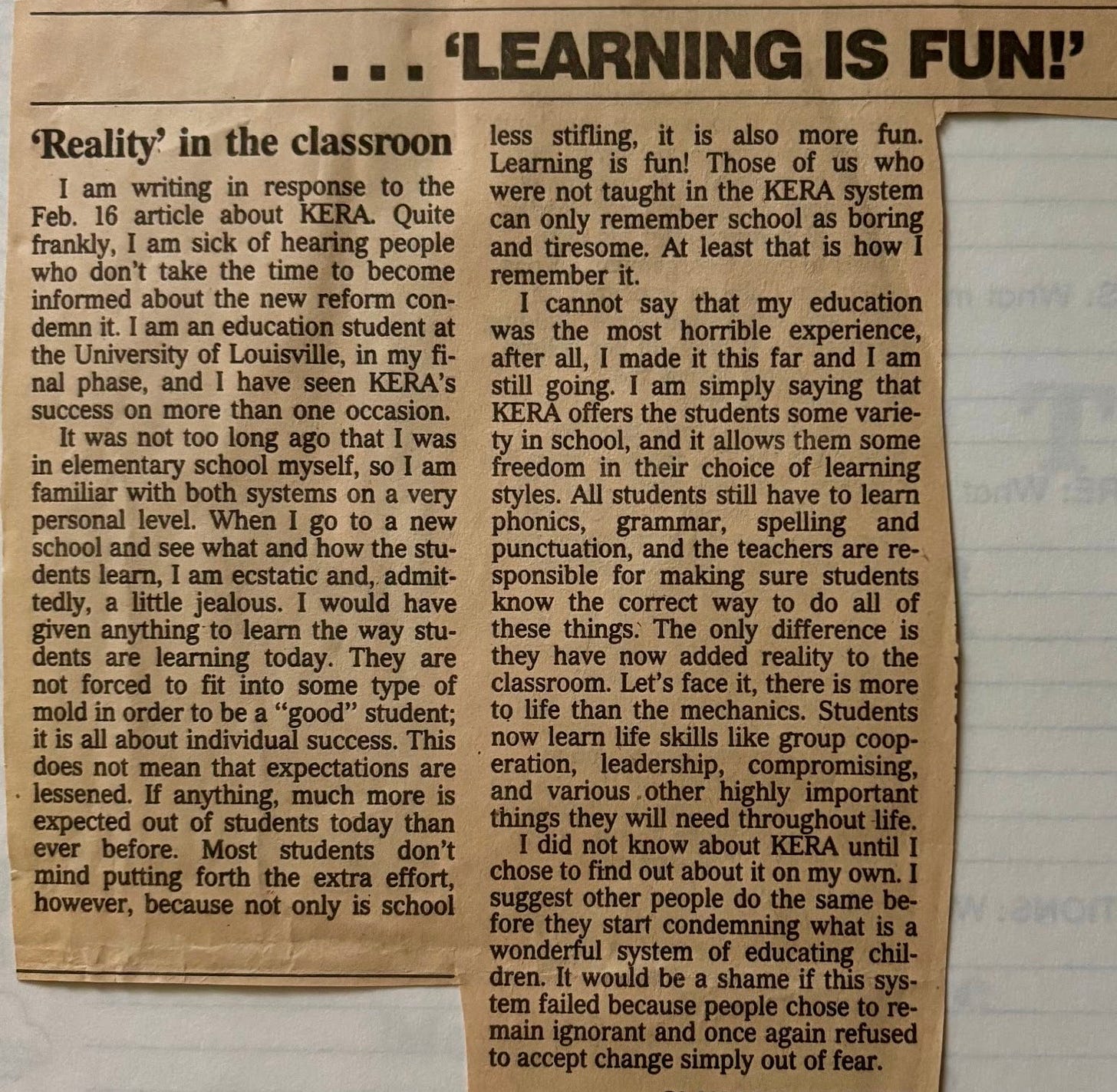

Thirty years ago, as a starry-eyed, (arrogant?), aspiring teacher, I penned a Letter to the Editor in support of the progressive education reforms in my home state of Kentucky. These reforms promised to “transform education” through “innovation”. I enthusiastically bought into all of the hype, even though it was the opposite of what I had known from my own education experience. Reflecting on the words I wrote in that letter three decades ago is a bittersweet exercise. I can appreciate the passion behind my words, but I abhor the ineffective teaching methods and ideas my words supported.

As I said, my own education looked very different from the one I was cheerleading for in the letter. From 1st through 8th grade, I received a rigorous, comprehensive, highly structured, and no-nonsense education at a private Catholic grade school. The public high school I attended for the next four years was primarily staffed with teachers who were considered “old school” and hadn’t been heavily influenced by progressive education ideas yet, so it was a fairly traditional education experience as well. My first encounter with the philosophy of progressive education was in college, and I was mesmerized and enthralled by it.

The idea that students should be “in charge” and that school could be fun was very alluring to a young, inexperienced aspiring teacher. It was like a child from a strict, authoritative home visiting a house where anything goes, and the children call their parents by their first names. The novelty of the lack of rules and structure is appealing, prompting the visiting child to question the rules-and-boundaries environment he is accustomed to and to desire the alternative. Later in life, age and experience bring an appreciation of what his parents did for him and of how boundaries and rules actually help children.

It took me a couple of decades spent in classrooms as a teacher and parent volunteer for the novelty of progressive education to wear off. Once it did, I could clearly see what my traditional, highly structured education had done for me, and that it is better for most children. It may not be flashy, but it is effective.

In addition to changes to funding distribution (which needed to happen) and graduation requirements (that diluted the significance of a diploma), the Kentucky Education Reform Act (KERA), passed in 1990, emphasized a “student-centered” approach that encouraged “innovation” and “creativity” from teachers to make learning “fun and engaging.” In plain terms, this meant a shift away from teacher-led classrooms, explicit instruction of content-rich curricula, and time-tested practices proven effective.

Like so many other naive young educators who knew only traditional teaching methods, I thought the grass would be greener on the other side. I was repeatedly told in my education classes that the societal issues many students faced would prevent them from learning in traditional classrooms. My professors insisted that strict classroom rules, teachers acting as authority figures, and rote learning were a hindrance to students from tough circumstances. I believed them, but they were wrong.

What I’ve learned over the past thirty years after working in classrooms, listening to and speaking with veteran teachers, and observing successful schools, is that students from all walks of life thrive when there are consistent routines, clear expectations, explicit, teacher-led instruction, and a content-rich curriculum. These are the very things that were dismissed or removed with the reforms that I so enthusiastically supported.

There are so many things I would like to tell the young lady who wrote that Letter to the Editor thirty years ago. One of the most important things I wish she’d understood is that knowing how to read, write, and solve math problems makes life fun, but learning how to do those things isn’t always fun, and that’s okay.

“You can’t go back and change the beginning, but you can start where you are and change the ending” is a quote often attributed to one of my favorite writers and thinkers, C.S. Lewis. Regardless of where it originated, it gives me hope that, even though I was part of the problem in K-12 education at the beginning of my career, I can be a catalyst in fixing it going forward.

‘Here’s what I used to believe about kids and learning and what I now know to be true’ will always be my favorite genre of Substack essay. Too few people are willing to look back at dogma they believed, examine it, critique it, and publicly throw it out and replace it with experience, data, truth and integrity . For me it was Unschooling. The “progressive education” of the homeschooling world. I believed so hard that a child would learn better if they came to the knowledge themselves through some gentle, often invisible, parental curating. Yeah, no. But this isn’t my essay, it’s your comment section. So I’ll save my novel. But keep sharing what you do! I think we’re getting somewhere with education, too slowly in regions like mine who are still fully using three cueing style “balanced literacy” methods in the primary years. But I see the momentum and it’s reaching progressive outposts like my area.

i enjoyed this, and your first-hand experience, as you may know, is backed up with a huge body of evidence now. Contrary to what the well-minded reformers believed, explicit instruction of content-rich curricula is the most effective teaching method, especially for children from less privileged homes. it's a shame that generations of children have been let down by the prevailing orthodoxy, but the tide seems finally to be turning!